Crops > Outlook & Prices > Outlook & Prices

May 2020

Another year, another crisis

For the last few years, it seems like agriculture has been running from one crisis to another. In 2018, it was the start of the trade fight with China and the spill- over skirmishes with the rest of the world. In 2019, it was the delayed and prevented planting problems across a wide swath of the United States. And in 2020, it is the coronavirus or COVID-19 outbreak. One was political or policy oriented; one was physical or weather-driven phenomenon; and the current crisis is a hybrid of both. While the virus and its spread are physical phenomena that directly impact agricultural production and consumption, the policy response has also led to significant changes in agricultural markets. The combination has forced most markets significantly lower, created sizable swings in price levels and volatilities, and left many farmers praying for a rebound.

The virus has taken advantage of our human need to interact with each other in order to spread. But those interactions also drive major parts of our economy. We travel for business and pleasure, going to conferences and vacations; we dine out for business lunches and family reunions; and we entertain ourselves in masse, at sporting events and concerts. The public health policy response to the virus has been to create physical distance between individuals in all social interactions, limiting the spread of the virus as best we can. That has led to the shutdown of most of businesses, a severe curtailment of business and personal travel, and a near- complete rescheduling of people’s lives. Business transactions and job requirements that could shift to an online environment did, while only those jobs and transactions deemed "essential" continued as close to usual as possible.

Thus, the damage to the demand side of the agricultural markets has been incredible. The closure of restaurants and the shift to significantly more at-home food consumption has driven a severe reworking of our food supply chain. The virus has struck at critical pinch-points in the food supply chain, our processing plants, creating imbalances between the farm and retail markets. Farm supplies remain large, as over the past few years, farmers and ranchers have produced record amounts of corn, soybeans, cattle, hogs, milk, poultry, and eggs. But the ability to translate those supplies to the food items we purchase at grocery stores has been noticeably reduced by COVID-19.

For crops, the impacts can be examined by exploring the three big sources of usage: livestock feed, biofuels, and exports. The impact of COVID-19 on feed usage is mixed. In the short term, feed usage will increase. We had and continue to have a large number of animals in the production chain. The sheer number of animals and the limits on alternative feed ingredients, such as distillers grains (we’ll get to that in a minute), have boosted direct feed usage for corn and soybeans. But in the longer run, the constraints at the processing plants are backing animals up, forcing producers to slow their herds and flocks down and reduce future animal numbers. That means less feed demand in the future.

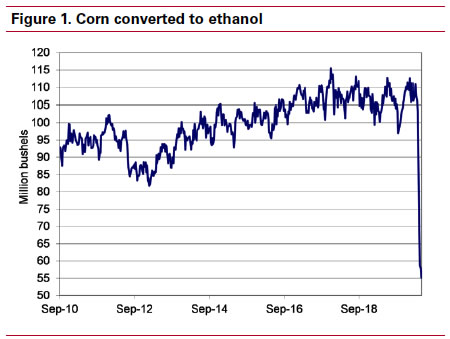

The impacts in the biofuel arena also contribute to the feed storyline. To put it bluntly, COVID-19 has cut the ethanol market in half. The severe reduction of ethanol production also means a severe reduction in distillers grains production. That reduction has forced many livestock producers to rework their feed rations, replacing distillers grains with other feed ingredients. To show how quickly farmers and ranchers have had to adjust, Figure 1 shows the weekly data for corn converted to ethanol (and distillers grains). Over the past couple of years, on average, over 100 million bushels of corn are processed by the ethanol industry. But within the past four weeks, corn processing at ethanol plants has been cut in half. Unlike at meat processing plants where COVID-19 hit the workplace hard, the ethanol plant closures have been driven by economic factors. Oil, gas, and ethanol supplies were at extremely high levels going into the COVID-19 outbreak. The “stay-at-home” and “shelter-in-place” orders, along with the general business shutdowns, drove the need for fuel in the US down to its lowest level in roughly 50 years. The combination of record supplies and minimal demand forced ethanol production to freefall and ethanol stocks to surge to record levels.

As businesses open back up, we can expect travel and fuel usage to increase. But it’s still an open question how quickly fuel usage will rebound. Even with some resumption of travel, it will take the ethanol industry some time to work through the ethanol already in storage, before reviving the shutdown plants. So both feed and fuel usage for corn are still facing tremendous uncertainty from COVID-19 impacts as we plant the next crop.

Exports have been the one usage area that has somewhat resistant to COVID-19. While export sales for both corn and soybeans were down, compared to last year, before the coronavirus pandemic, export sales during the outbreak have kept pace or exceeded last year’s pace. Corn export sales before the outbreak were already 500 million bushels behind last year’s sales pace. The trio of a strong US dollar, weaker global economies, and ample global supplies provided several good reasons for the sales drop. Since then, however, corn sales have perked up, with the gap shrinking to 366 million bushels with the latest weekly export sales report. Figure 2 outlines the sales changes this year. While most corn markets are still in negative territory, the numbers have been moving towards zero. With the signing of the Phase 1 trade deal with China, China has emerged as a growth market for US corn. Currently, China is our 6th largest buyer of corn, up 85% from last year. We have also seen some gains in smaller corn markets, represented by the “Other” bar in the graph. That bar was down nearly 80% a few weeks ago, recovering to down 36% now.

Soybean export sales have been treading water during the coronavirus outbreak, as total sales have remained around 225 million bushels behind last year’s pace. But this week’s sales report does show China and Egypt are starting to be more aggressive buyers. While China captures the lion’s share of attention in the soybean market, it’s the move by Egypt that caught my eye. Egypt tends to move in and out of ag markets to take advantage of low price opportunities (think of them as Walmart shoppers, following Walmart’s old slogan “Always Low Prices”). Well, US soybean prices have moved low enough to stir up some international demand.

Putting this all together, futures prices at the end of April pointed to the following. For the 2019/20 crops, previous sales during the fall and winter are now being undercut by sales this spring following COVID-19. The 2019/20 season-average price estimates currently stand at $3.52 per bushel for corn and $8.55 per bushel for soybeans. New crop price estimates started the year near $4 for corn and $9.50 for soybeans. Now, corn is basically at breakeven (ISU corn production cost estimate was $3.32 per bushel) and soybeans has slipped well below breakeven at $8.31 per bushel (ISU soybean production estimates was $8.72 per bushel). I think the first chance to regain some of that lost profitability will come later this month or early next month. Seasonally, mid-June is when we tend to see our highest prices. Also, if the partial reopening of the economy can continue, that could provide some additional lift then.

Beyond that, expect lower price through the latter part of summer, especially given the planting pace so far this spring. It looks like there will be plenty of acreage in play for harvest this fall, and that usually translates into plenty of bushels. More robust price recovery will take some time to develop, like the vaccine for COVID-19, it could take a year or two.

Chad E. Hart, extension economist, 515-294-9911, chart@iastate.edu