Maureen Moroney

The debate about terroir, what it is or isn’t, where it comes from, or whether it even exists at all, seems to be a perpetual one in the world of wine.

Recently when I was scrolling on social media, I came across this post:

Read the article here: https://daily.sevenfifty.com/why-native-yeast-fermentations-are-critical-for-expressing-terroir/

SevenFifty Daily typically has pretty good practical break-downs of scientific topics, and I consider it a valuable resource, so I was curious to read further. (After all, who wouldn’t want to see the data that could “revolutionize” winemaking?!?)

Unfortunately, the story itself was short on data and details. After reading it (a few times), and checking for embedded links that might help provide a more complete picture, I found myself with more questions than answers. It’s entirely possible this is the beginning of some great new insight into the potential of microbial terroir… but it’s impossible to tell based on the information provided.

Summary of the article’s main points:

- New facility, all concrete. Pressure-washed floors and walls. Sent samples of one wine “at the beginning, middle, and end of fermentation” to ETS.

- “The results confirmed that native yeasts are indeed fermenting our wines.”

- High population diversity, no clearly dominant strain.

- Native yeasts present throughout the length of fermentation (10 strains persisted throughout).

- ETS staff suggested that yeasts might have come from previous occupants, used barrels, shared equipment, or nearby facilities.

- “Most of the time, wineries build up their own microflora, including yeasts and bacteria. [ETS] has seen wineries—ones that have never used commercial strains—ferment wines solely through populations of native yeasts that exist in the wineries.”

My main questions during and after reading:

- Were grape samples sent directly from the vineyard to have their yeast populations analyzed, or only after the fruit had been processed at the winery?

- Where is the actual data? It’s typical for diverse populations of yeast to be present throughout a fermentation, so what was the population breakdown in this wine?

- When the article uses the word “native,” what exactly does that mean? (More on this question, below.)

In order to dig into these questions, we need to talk a little bit more about wine yeasts, in general.

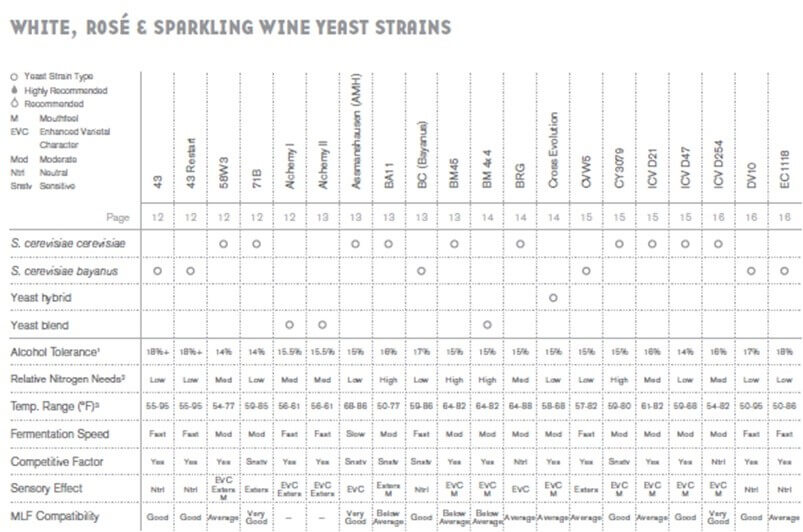

First, let’s focus just on commercial yeasts, which have been selected for specific characteristics. Commercial yeasts contain only one specific strain rather than a mixed population, they’re relatively distinct from one another, and their behavior is relatively predictable. The ways commercial strains differ from each other may include: sensory characteristics of the wine (flavor, aroma, texture), fermentation speed, nutritional requirements, and tolerance of chemical parameters (such as alcohol and pH).

(Chart from Scott Labs. Full PDF here: [Yeast_Selection_Chart.pdf])

There are plenty of yeasts floating around in the environment all the time, the vast majority of which are not identical to commercial wine yeasts, either genetically or in the traits they express. So it is entirely possible to have juice or must start to ferment without adding any yeast to them. This would be an un-inoculated fermentation. Just like commercial yeasts, other types of yeast present in the environment have their own characteristics, and can have different effects on wine.

Where things start to get fuzzy is that there are a lot of ambiguous terms associated with un-inoculated fermentations, including “wild,” “native,” “spontaneous,” “indigenous,” and even “ambient.” When we say “native fermentation,” do we simply mean fermentation that was conducted without intentionally adding a specific yeast? Or is it meant to imply that the yeast doing the fermentation came in on the grapes? If the yeast was picked up in the winery facility, and it happens to belong to a commercial strain, but it wasn’t intentionally added, is that a “native” fermentation or not? If a yeast strain found in wine doesn’t belong to a commercial strain, does that mean, by definition, that it is “native”?

For un-inoculated yeast strains that come from the winery facility rather than the vineyard, it seems misguided and confusing say that they are a reflection of “terroir” or to attribute “terroir” to their influence.

And, to complicate matters further, the yeast that is (or isn’t) added to must or juice is often not the only or the dominant yeast over the course of the fermentation, whether you inoculate or not.

As an example of a typical yeast population during fermentation, let’s look at the figure below. The first three fermentations (shown in A, B, and C) were inoculated with commercial yeast RC212 (shown in red). The last fermentation (D) was un-inoculated and allowed to begin spontaneous fermentation. The four bars on each chart show samples taken at four time points during each fermentation: Cold soak (CS), Early fermentation (EF), Mid-fermentation (M), and End of fermentation (F).

At cold soak (pre-fermentation), the dominant yeast strain in all four fermentations is H. uvarum (in blue), which is a true “native” yeast present in large numbers on grapes in the vineyard. H. uvarum has a low alcohol tolerance, and is quickly out-competed by yeast strains that can tolerate the alcohol being produced.

Another thing to note is that, while the first three fermentations were all inoculated with RC212 (in red), it’s not the dominant yeast strain at any point during the first two fermentations. Also important is the fact that all four of the fermentations show a mixed population of yeast strains even at the end of fermentation. Lastly, in fermentation D, which was un-inoculated, the identities of the dominant yeast strains turned out to be RC212 and D254, which are both commercial wine yeasts. This is often the case with un-inoculated wines: they may begin to ferment spontaneously, but the yeasts doing the work are whatever was already present in the winery, not yeast strains that came in with the grapes.

So, there’s debate about how much control a winemaker has over what yeast strain does (or doesn’t do) the majority of the fermentation. But even if you could perfectly control it, how much difference does it really make?

The article mentions that the winemaker believes a diverse population of native yeast contributes to a more complex, higher quality wine. It seems fair to speculate that a more complex microbial population would yield more complex flavors and textures in the wine. Here again, we run into ambiguity about whether that complexity is due to “native” yeasts, or to a mixed population in general, or to other related factors (which we’ll come back to in a minute), or some combination of all of the above. If a mixed population of yeast is truly the key, then that seems to be achieved even when commercial yeast is added; “minor” yeast strains are still present, and could still contribute to wine flavor in noticeable ways in much the same manner as they would in un-inoculated wines. On the flip side, even commercial strains that are specifically selected for particular characteristics may not deliver those results in a way that consumers can consistently distinguish.

Yet another complicating factor in all of this is that some major differences between yeast strains (whether commercial or ambient) are their fermentation dynamics and their tolerance for environmental conditions. A yeast that ferments extremely quickly will cause the wine to reach a higher fermentation temperature than a slower fermenter will, which can in turn influence sensory properties of the wine. An un-inoculated wine may have a unique fermentation curve compared to an inoculated wine, which may be due in part to the innate characteristics of the strains present, but is likely also a result of the fact that inoculation adds about 5 x 10^6 yeast cells/mL (or 18,925,000,000

yeast cells per gallon). Plus the same yeast strain under different environmental conditions (such as high temperature or high brix) may have a stress response that will cause it to produce different flavor compounds than it would under normal conditions. So it’s difficult to pick apart what properties in the wine are a result of the yeast strain, which are influenced by other factors, and which are caused by the interaction of biological and abiotic factors.

(Image credit: Doug Pike)

While the topic of so-called “native” yeast is a murky and tangled one, and we can’t pinpoint their effects, it is clear that there are some differences between un-inoculated and inoculated fermentations. So if you, as a winemaker, have had successful fermentations without inoculating and you like the wines that result, that’s great and you should stick with what works best for you.

If you are a winemaker thinking about trying an un-inoculated fermentation, here are some points to keep in mind:

- One key reason for inoculating with commercial yeasts is to get the fermentation started right away, in order to limit the opportunity for spoilage microbes to get established. With un-inoculated fermentations, it’s likely to be a few days before a spontaneous fermentation becomes active, leaving a wide window for spoilage to get a foot-hold.

- Use only clean, intact grapes. Do not attempt an un-inoculated fermentation on low-quality fruit.

- Consider a significant dose of sulfur dioxide immediately after fruit processing to knock back populations of spoilage organisms. Unfortunately, this may also reduce the number of naturally-occurring yeast, but the larger concern at this stage is likely to be acetic acid bacteria.

- As always, good winery sanitation is essential.

- When you aren’t in control of the timing, number, or type of yeast cells being added, it makes the fermentation dynamics less predictable.

- Close monitoring and control of temperature is important. Keep temperatures low early to discourage spoilage before fermentation starts, let the fermentation warm up as it gets going to encourage healthy yeast, make sure it doesn’t overheat as fermentation peaks, then keep warm through the end of fermentation to avoid a sluggish finish.

- Similarly to temperature, oxygen management is important. Exclude oxygen early, allow some during fermentation to keep yeast healthy and prevent stress, and then minimize oxygen exposure as fermentation nears completion.

- Un-inoculated yeasts need nutrients just like commercial yeasts do. Make sure the Yeast Assimilable Nitrogen level in the must or juice is sufficient, and make additions if necessary.